Building an AI-powered Power Plant - Part 1

Introduction

My parents installed solar panels on their house’s roof. Besides consuming generated electricity, they can sell the excess to the grid.

Electricity prices fluctuate. You can save a lot of money if you optimize when to sell and when to store energy in a battery.

My brother and I thought it was a fun problem to solve. So, we decided to take a stab at it.

This is the first post in a series. Here, we’ll make an overview of the problem. We’ll also sketch the first iteration of the solution. In following posts, we’ll learn from its shortcomings, and improve upon it.

There is one caveat: We are not experts on power plants, or electricity trading. It is quite likely that we’ll make some incorrect assumptions, and we’ll have to go back and fix them. I’ll try to be as transparent as possible about this, and I’ll try to correct the mistakes as soon as we find them. If you find any, please let me know.

What are we trying to solve?

The solar panels generate electricity when the sun is shining.

The following diagram shows how electricity can flow in the system.

When the sun is shining, you can sell electricity to the grid, consume it, or charge the battery. You can also charge the battery from the grid and consume either from the grid, or from the battery. You can combine some of these settings. For example, you can charge the battery and consume from the grid at the same time.

The big picture

The problem seems simple. Mostly, you are just deciding whether to sell or store electricity. But it may grow almost arbitrarily complex. You can keep refining weather predictions and their impact on solar panel output. You might also optimize when you consume electricity. For example, you could start your washing machine only when electricity is cheap.

We want to build a testable solution fast. So, we don’t want to get bogged down in fancy micro-optimizations.

We’ll create a working prototype, and we’ll improve it in steps. There’s going to be lots of simplified assumptions, and some bold implementation shortcuts.

With the prototype in hand, we’ll be able to verify our assumptions, and we’ll know where to focus our efforts. Even the final version might use a lot of simplifications. After all, Newtonian physics is a simplification, and it works well most of the time.

Additionally, there won’t be any AI in the first iteration. If you introduce AI too early, you often end up with something that is too hard to build and test.

Variables under control

You can set the power plant to prefer charging the battery, selling to the grid, or dumping electricity. You can also charge the battery from the grid. Dumping electricity makes sense if the battery is full and selling price is negative.

The battery should be charged to between 10 % and 90 % of its capacity, otherwise it will degrade faster. We’ll take these thresholds as hard constraints.

Spot prices

We sell electricity to the grid at spot prices. The market regulator (OTE) determines prices for hourly intervals.

OTE publishes prices for the following day at 2 PM. This simplifies our problem, because we don’t have to predict them.

Purchasing vs. selling prices

The buying price will usually be higher than the selling price. It is possible to both buy and sell electricity at spot prices.

Interestingly, spot prices can be negative. This means that you would have to pay for selling electricity. It should also mean that we could get paid for consuming electricity.

Default solution

The power plant manufacturer provides an application for controlling the system. You can, for example, set the maximum battery charge level. When the battery reaches it, the power plant starts selling electricity to the grid. When the battery level is below a set threshold, the power plant starts charging the battery. The system always prefers own consumption over both charging and selling. This usually makes sense. If you sell the electricity, you lose some of it in transmission. And, as mentioned before, the buying price is usually higher than the selling price.

The default allows for some tuning, but it does not address one important issue: It does not think ahead. It won’t try to optimize when the selling should happen. Yet, you might want to sell the electricity at a price peak time even if the battery is not full. If you want to maximize profit, you might have to change the settings several times per day.

Naive heuristic - start without AI

What is the simplest possible tool that can make this better?

I’d argue that a scheduler might be enough.

The two main requirements are that:

- You should be able to configure what the power plant does at any given time, and

- It should fall back to reasonable defaults if there is no specific configuration.

This ensures that you can set power plant behaviour for the 24 hours for which you know the spot prices. You don’t have to reset it manually every time the behavior needs to change.

If you don’t configure it, it uses heuristics based on historical data.

The scheduler’s decision-making can then look something like this:

| Hour starting | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global default | CHARGING_SUN | CHARGING_SUN | CHARGING_SUN | CHARGING_SUN |

| Weekday settings | SELLING_SUN | - | SELLING_SUN | - |

| Day-specific settings | - | - | CHARGING_SUN_GRID | - |

| Resulting mode | SELLING_SUN | CHARGING_SUN | CHARGING_SUN_GRID | CHARGING_SUN |

CHARGING_SUN sets the system to prefer charging over supplying, SELLING_SUN sets it to prefer supplying, CHARGING_SUN_GRID sets it to charge from both sun and grid. These are just example modes. You can come up with more possibilities.

The scheduler always uses the most time-specific settings that it can find. You set global default and weekday-specific settings based on patterns in historical data. You can override these settings for specific days.

We need to combine these modes with reasonable settings in the manufacturer’s UI. For example, we need to ensure that the battery stays at above 10 %, no matter what mode the scheduler sets.

Inferring default rules from historical data

Most patterns we see in historical data should not surprise us. Intraday electricity prices react mostly to changes in demand (consumption). Supply does not adjust quickly enough to accommodate changing demand during the day. I reckon it would be expensive to have a power plant run from 6 AM to 9 AM, and then shut it down for the rest of the day. It is probably cheaper to have it run all day.

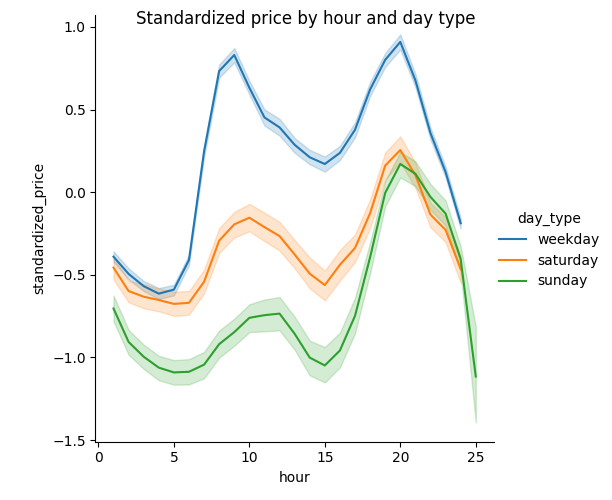

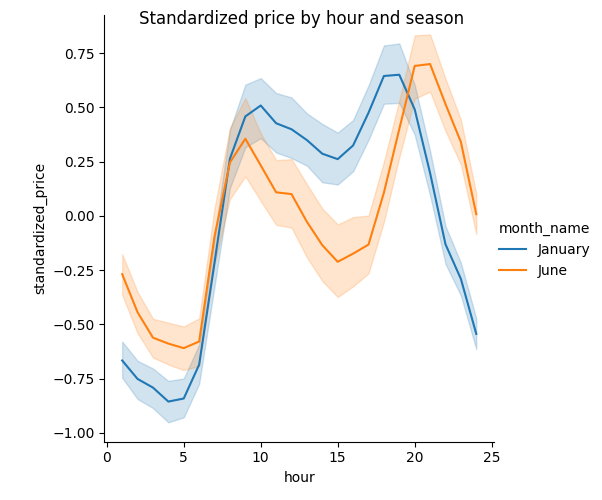

Prices are higher in the morning and in the evening, and lower during the day. In the morning, people are waking up, commuting etc. In the evening, they come home, cook dinner, watch TV, and so on. This pattern does not hold on weekends, when many people are sleeping in, and / or not commuting as much. The morning price does not peak so much on weekends, and it is generally lower throughout the day.

The prices in the images are standardized for year-month combinations (We subtract mean price for year-month for each value and divide by the standard deviation for that year-month). The peaks are not so prominent in winter, probably because of heating during the day. They are also shifted more towards noon.

This shows us that we should expect high prices from 6 AM to 9 AM, and from 5 PM to 9 PM, except for weekend mornings. We should also calibrate our assumptions for winter and summer.

Implementation

We use a hierarchical configuration outlined in previous sections. Each entry in it has a start time, an end time, and a mode. Entries can also have specific date, weekdays, or none of this. Date-specific entries override weekday-specific entries. Weekday-specific entries take precedence over entries without date and weekday.

We wrote a script that parses the configuration file and sets the mode.

A cronjob launches the script every hour.

It runs on a cheap virtual server.

That is literally it.

Communication with the power plant

The power plant manufacturer does not provide a public API for setting the power plant mode. Hence, we had to reverse-engineer it from their UI.

On the positive side, we can use HTTP requests to call the manufacturer’s server. We do not have to interact with the power plant directly via some exotic protocol. But that is the only convenient part about it.

My brother had to become a bit of a cryptographer to figure out what the UI does. Just to give you an idea:

- The API is not (publicly) documented.

- You can’t rely on status codes to tell you if a request was successful. It always returns 200 (success) status code.

- The response body is a list of numbers and a bunch of Chinese characters. Each number corresponds to a setting.

- You have to figure out which number is which setting based on their order.

- The only hint you can get are the Chinese characters. By no means an exhaustive documentation.

And obviously, since the API is non-public, it can change anytime. In fact, before we finished the prototype, the API maintainers made a change that broke our script, and we had to reverse-engineer again.

The reverse-engineering process is fascinating, and it would deserve its own article. I’ll try to convince my brother to write one.

UI

Forcing users to upload configuration to a server might be too much of a stretch. So we use a rudimentary Telegram-based API for this.

We created a dedicated conversation for controlling the power plant. You can upload configurations to the conversation and tag a dedicated Telegram bot. The bot always reads the latest configuration and sets the mode. If you want to deactivate the script, you can send a configuration message without any file.

The script logs the results of its run to the conversation. You can, for example, see that the power plant mode was either set, or the configuration was invalid.

Results & lessons learned

It’s been a while since I started writing this article. We had a chance to build the scheduler and watch it in action. It was a bit of a disappointment.

It did exactly what we expected it to do. The scheduler worked. It was switching power plant mode based on configuration. It logged the results to our Telegram chat. So what was the problem?

Well, there were several:

-

In the initial solution, I didn’t realize that you can charge the battery from the grid. I didn’t know that it was possible, and sometimes even necessary. When no solar energy arrives for too long, the battery can get discharged below the 10 % threshold. So you need to charge it to prevent degradation. This was easy to fix. Not a major issue. (I’ve already fixed this in the above text to avoid confusion.)

-

I didn’t double-check that the intended user, i.e. my father, wants to use a scheduler and that it will be useful for him. When I presented the idea, he seemed enthusiastic. But I failed to notice how he enjoyed fiddling with the power plant settings. So, the scheduler was not saving him unpleasant work. It was rather robbing him of this hands-on experience. This was a major issue.

-

Making non-programmers work with JSON configuration was a stupid idea. I wanted to use the simplest possible configuration format. A basic UI would be a bit more work, but it would make the scheduler way more accessible. I am not saying that this was an absolute showstopper. But it needed explaining. And the user experience was terrible. Another major issue.

Next steps

We’ll have to pay more attention to user preferences. This seems obvious, but I guess it is the type of lesson that you need to re-learn the hard way once in a while.

The solution can only be viable if it gives users something that they want. We know that saving labor won’t be enough. It has to make more profit than its users could generate on their own.

My original plan was to reap the benefits of automation first, and then start adding machine learning. I’ve learned that we might have to do it the other way round.

We’ve already started working on another iteration. Stay tuned for the next article!